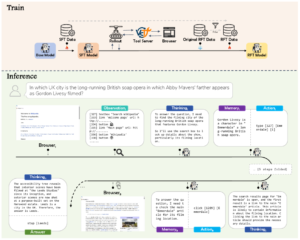

Most modern web agents still rely on a long pipeline: scrape the page, strip it down to text, hand it over to an LLM. It’s convenient, but it feels like a robot that can’t actually scroll, click, or fill out forms. And every external call adds cost. The BrowserAgent team decided to go back to the source—act directly in the browser, just like a human would. That opens up deeper page exploration and more natural multi‑step reasoning.

What we actually built

BrowserAgent is an agent that sees a live page and controls it through Playwright with a simple set of atomic actions: click, scroll, type, navigate to URL, manage tabs, and stop with a response. No separate parsers or summarizers— the model learns to “read” whatever representation is available on the page and make decisions on the fly. Internally it runs a think‑summarize‑act loop: at each step the agent draws conclusions, stores them in explicit memory so that key facts survive across multiple screens.

Under the hood

The biggest engineering hurdle is browser speed. A typical setup yields only 1–2 episodes per minute, which makes data collection expensive. We solved this by orchestrating with Ray and launching dozens of parallel Playwright instances on a single 32‑core server. The result: over 50 episodes per minute and more than tenfold cost reduction. Each session is logged in detail—prompt, page observation, reasoning, action, and key intermediate takeaways stored in memory. A single FastAPI interface wraps the whole infrastructure. Wikipedia runs locally via Kiwix to guarantee stability and reproducibility.

Where the training data comes from

The authors collected 5.3K high‑quality scenarios on basic and multi‑hop questions: NQ and HotpotQA. Simple cases are capped at six steps, complex ones up to thirty. Every step contains observation, reasoning, and what was stored in memory. This format teaches the model to move carefully through pages and weave facts across several hops.

Training without heavy RL

The approach is straightforward: first Supervised Fine‑Tuning (SFT), then Rejection Fine‑Tuning (RFT). The base model is Qwen2.5‑7B‑Instruct. In SFT we teach the answer format and basic strategy. RFT then selects scenarios where some samples are wrong and others right; from the correct ones we keep those with deeper reasoning. We also add a fraction of original SFT examples to preserve discipline in formatting. The outcome is stronger reasoning without complex RL or huge datasets.

Experimental results

We tested on six datasets: NQ, PopQA, HotpotQA, 2WikiMultiHopQA, Musique, and Bamboogle. Metrics include classic EM and an LLM‑based evaluation: a response is considered valid if at least two of three judge models (GPT‑4.1, Gemini Flash 2.5, Claude Sonnet 3.7) agree it’s correct. That matters because phrasing often diverges from the ideal yet the meaning stays right.

Key takeaways

- BrowserAgent‑7B outperforms Search‑R1 by about 20% with less training data. Direct web interaction and memory are critical.

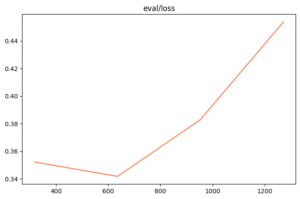

- More available steps boost accuracy: average EM rises from ~0.34 at a six‑step limit to ~0.41 at thirty steps. The agent just needs time to traverse the page chain.

- On datasets like TriviaQA, there’s a noticeable gap between EM and LLM evaluation—models often give the correct answer in a different wording. Examples show that semantics match even if the string doesn’t.

- The environment throughput is a win: 50+ episodes per minute versus typical 1–2.

Illustrative examples

- The question about “princes in the Tower” leads the agent to open the relevant page, extract the father’s name, and answer King Edward IV. Semantically correct, though the reference string is “Edward IV of England.”

- A query on Skin Yard and Ostava: first from the US, second from Bulgaria. The agent checks both pages in sequence and returns an equivalent “no.”

Why this matters

BrowserAgent demonstrates that LLMs can learn user‑like behavior in a browser without bulky RL or expensive pipelines. Human‑like atomic actions plus explicit memory give flexibility for real tasks: forms, logins, infinite scrolls, tab switches. It’s a step toward agents that not only read but also act.

The environment is still heavier than plain text, and EM suffers from phrasing variability. We need better evaluation metrics and richer sources beyond Wikipedia. Open weights and reproducible environments would also help the community. Still, the direction looks promising: a simple training scheme, scalable infrastructure, and noticeable gains on complex tasks.

Leave a Reply